Here's a clip from one of the lesser-know Paisley bands, similar to The Bangles, but without the same level of mainstream ambition (which is a compliment)...on a side note, ever heard Mojo Nixon?

Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Wednesday Week- "Why" Video (1987)

(La) luna Lexicon:

1980s,

Indie,

Jangle-Pop,

L.A. Underground,

Paisley Underground,

Power-Pop,

Video,

Wednesday Week

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

Josef K- The Only Fun in Town (1981) / Sorry for Laughing (1990) / Young and Stupid (1987) MP3 & FLAC

"So I'll disappear through the crack in the wall, and the memories I leave

will be nothing at all."

will be nothing at all."

Despite Josef K's brief existence (they decided to disband after releasing only one album), they proved to be one of the more influential bands of their era, which only serves to remind what a dynamic and utterly unpredictable time Post-Punk's early years actually were. Staunchly unconventional, the band formed in 1979 and almost immediately became a charter member of the burgeoning Scottish Post-Punk scene, especially after signing with Postcard records, a legendary Scottish indie label run by Alan Horne who also issued Orange Juice's early singles. Josef K frontman Paul Haig: "Alan Horne was desperate to become Scotland's answer to Andy Warhol, and Postcard Records was more conceptual than corporate. Really, Alan kept a few papers in a top drawer in his flat- that was Postcard [....] There was some pushiness from him to be more accessible, like Orange Juice. He really didn't like our trebly guitars and our noisiness." Despite Horne's reservations about the commercial viability of the band's sound, Josef K released several critically-lauded singles before recording their debut album, Sorry for Laughing, in late 1980; however, on the eve of the album's release the following year, the band decided to scrap it, claiming the album sounded too polished. In actuality, Sorry for Laughing, though not representative of Josef K's live sound at the time, did seem to open up a number of new sonic vistas for the band, as it tempered their trademark abrasiveness a bit in the service of a slightly more arty and fully-formed sound. On the title track, the band comes across as something like a version of Joy Division with grander pop inclinations, and on the stunning, "Endless Soul," Josef K edges into territories unknown as they carve out an abrasively poppy sound that proves to be a heady counterpoint to Haig's nervy croon. Now without an album to release, the band returned to the studio and hammered out The Only Fun in Town in less than a week. Haig: "When we recorded The Only Fun in Town, we wanted to keep our live sound as much as possible. We thrashed it out in a really short time- it only took six days- and on purpose we mixed the album low because we wanted to keep that live feel, which again in hindsight was pretty stupid. Afterwards we made things slightly more polished, but the album was still pretty abrasive." Whereas Sorry for Laughing suggested a band edging toward a slightly more open, approachable sound, The Only Fun in Town is a torrid and uncompromising blast of trebly alienation. On lead track "Fun 'n Frenzy," a spidery Television-inspired lead guitar figure is counter-balanced with some dissonant chording from the rhythm guitar, setting up a strange, almost surf-rock feel for Haig's razor's edge croon. One of the re-recorded songs that benefits greatly from the less-polished approach of The Only Fun in Town is "Sorry for Laughing," which, while certainly sounding more shambolic, contains one of Haig's best vocal performances- he is far more convincing here than on the earlier version. Ironically, after having gone to the trouble of recording a new debut album because the original, according to Haig, sounded "flat and disinfected," the new album was roundly panned by the critics, with NME actually claiming, "Josef K have cheapened themselves and cheated the world." The band dissolved soon thereafter, but in another ironic twist worthy of their name, twenty years later they became one of the most influential bands of the original Post-Punk era. Haig: "Josef K were the ultimate band for me. It was so intense, a way of life, a very special thing. And that's proved by the fact people are still interested in what we did."

(La) luna Lexicon:

1980s,

Album,

Art-Rock,

Compilation,

FLAC,

Josef K,

MP3,

Orange Juice,

Paul Haig,

Peel Sessions,

Post-Punk

Monday, August 29, 2011

Elvis Costello and The Attractions- "(I Don't Want to Go To) Chelsea" Video (1978)

What's better than early Elvis? (Costello that is). I really like the guy's twitchy insolence in these early clips. Why do people have to get old?

(La) luna Lexicon:

1970s,

Elvis Costello,

Post-Punk,

Punk,

Singer-Songwriter,

Ska,

Video

Sunday, August 28, 2011

Paisley Underground Series, #22: The Dream Syndicate- Medicine Show (1984) / This Is Not the New Dream Syndicate Album...Live! (1984) MP3 & FLAC

"I got some John Coltrane on the stereo baby, make it feel all right. I got some fine wine in the freezer mama, I know what you like."

The Dream Syndicate's debut LP, The Days of Wine and Roses, is justly considered to be one of the best neo-psych albums released during the eighties, a dark, feedback-drenched love letter to The Velvet Underground and Television that quickly catapulted the band into the forefront of the emerging L.A. Paisley Underground scene only nine short months after they had come together in Davis, CA. As lead vocalist and guitarist Steve Wynn recalls, "It was an overnight thing. There was no dues paying. It was very weird and it screwed us up in some ways." One negative consequence of producing a masterpiece their first time out is that the band's later work has tended to languish in the long shadow of their formidable precursor. In the aftermath of their early brush with success, change settled in on The Dream Syndicate. First, their bassist and sometime vocalist Kendra Smith left to join boyfriend and ex-Rain Parade guitarist David Roback to work on his Rainy Day project (she was replaced by former Al Green bassist David Provost). In addition, the band was signed by a major label, A&M Records, and thereafter quickly set to work, with former Blue Oyster Cult, Dictators, and Clash producer Sandy Pearlman, on what would become their most divisive and misunderstood record, Medicine Show. This album has tended to garner charges of being a major label sellout, and while it is certainly more polished than the band's debut (which is to be expected), it is anything but a play for mainstream success (unlike fellow Paisley Underground figureheads The Bangles). Rather, Medicine Show captures a young band finding their way as mature songwriters. Steve Wynn: "I'd written a lot of songs before Wine and Roses, but the storytelling, the larger scale, taking a frozen moment in time- it all started on this record." The band was also dealing with their meteoric rise from feeling fortunate if they got third billing at the L.A.-area clubs they were playing to suddenly being the headliner: "Defiance, fear, apprehension- they were all happening to us by then, and a lot of that came out on the record. It's in the songs, in the sound." By all reports, Pearlman drove the band hard, insisting on take after take until the performances reached a raw state of emotional honesty, an approach that served Wynn's dark, sometimes violent lyrical content well. The album's terrific opener, "Still Holding on to You," which has a faintly similar vibe to the debut album's "Tell Me When It's Over," sets the tone for the entire album with its tale of inconsolable loss and emotional desperation. While the band is still conjuring the ghosts of The Velvets here, there is a new-found confidence and a more open sound that lends the song a rootsy feel reminiscent of Neil Young. Medicine Show concludes with two epics: "John Coltrane Stereo Blues" and the stunning "Merrittville," which Wynn has described as "the Book of Job in eight minutes." The latter sounds something like The Church jamming with Crazy Horse, and is a heady reminder of just how misunderstood and criminally underrated this album is. Steve Wynn: "Karl [Precoda] wanted to make a big, panoramic rock record to justify our move to a major label and the plethora of attention we had received in the mere nine months that had passed since the release of The Days of Wine and Roses. I wanted to make a 'beautiful loser,' button-pushing, over-the-top emotional catharsis in the tradition of most of my all-time favorite records (i.e. Big Star 3rd, Tonight's the Night, Plastic Ono Band, etc.). We both got our way- and in ways that neither of us could have predicted. I think it was this improbable collision of desires and personality that gives Medicine Show its character."

(La) luna Lexicon:

1980s,

Album,

Americana,

Compilation,

Danny and Dusty,

Dream Syndicate,

FLAC,

Jangle-Pop,

L.A. Underground,

MP3,

Paisley Underground,

Psychedelic,

Steve Wynn

Saturday, August 27, 2011

Josef K- "Sorry for Laughing" (1981) Live TV Appearance, Belgium

The greatest "one and done" band of the original Post-Punk era. Ah, I remember my Kafka/ Hamsun / Dostoyevsky period quite well...

Friday, August 26, 2011

The T3@rdrop Expl0des- Kilim@nj@ro (1980) Deluxe Edition (3 Discs) MP3 & FLAC

"You wandered into my dreams last night, and you stood them all up in a row. You trampled all over them with stones in your shoes, and you said, 'Oh yeah, I thought that you'd know.'"

Julian Cope on the transitory nature of The Teardrop Explodes: "The band was never built to last [....] it was like building a house on scaffolding on top of a tank moving at three miles an hour. The higher you build it, the further removed you are from the reality that it's actually moving and going to fall." Before forming The Teardrop Explodes, Cope had experienced several false starts in his effort to jump-start a music career in late-seventies Liverpool, including a band called A Shallow Madness, which also featured Ian McCulloch, who, after being ejected from the band due to ego clashes with Cope, would later become one of the pivotal figures of the Post-Punk movement as a member of Echo & The Bunnymen. After a few additional personnel changes, Cope renamed the band The Teardrop Explodes (inspired by a panel caption in a Marvel comic strip) and began to explore a sound that would, in many ways, run counter to the prevailing trends embraced by the Post-Punk movement. By integrating neo-psychedelia into the band's sonic palette and indulging in his love of Kraut-Rock, Cope showed signs, very early on, of the eccentricity and iconoclastic nature that would later come to define his career. As the quote above suggests, The Teardrop Explodes seemed to function creatively through internal strife and dissension, which resulted in a very unstable lineup throughout the life of the band and Cope's growing reputation, thanks in part to McCulloch's constant personal attacks in the music press, as being something of a tyrant to work with. In truth, Cope was a workaholic who had little patience for what he perceived as a lack of motivation on the part of band-mates. After releasing a couple of singles, The Teardrop Explodes recorded their debut LP, Kilimanjaro, which was, true to the band's nature, a process riddled with conflict and change. A prime example was the sacking of the band's lead guitarist for "complacency" and replacing him with Alan Gill, who soon introduced Cope to the use of psychotropic drugs, something that quickly became a heavy influence on his work. Musically, Kilimanjaro was one of the most distinctive albums to emerge from the early Post-Punk movement, as it clearly demonstrates the moody neo-psych sound that characterized the Liverpool scene of that time but also exhibits then-unconventional tendencies such as poppy melodies and some very un-Post-Punk song arrangements that occasionally include trumpets reminiscent of the brass flourishes employed by late-sixties psych bands such as Love and The Doors. And then there's Cope's distinctive voice, which, on songs such as the opener, "Ha Ha I'm Drowning," traverses the same emotive territory as that of his arch-rival McCulloch, except that Cope's voice has a sweet resonance that recalls Scott Walker at times. Vocals aside, Kilimanjaro is also full of quirky melodic twists and turns that lend it its singular sound. A perfect example is "When I Dream," an impossibly catchy song built around Cope's tongue-twisting chorus, while musically, the keyboard washes and percussion that characterize the song recall middle-period Japan with their vague World-Beat references married to a New-Wave aesthetic; however, the results are far more pop-oriented than Japan's mannered experimentalism. Julian Cope during his tenure in The Teardrop Explodes: "I think we're very poppy. To me pop is something you hum. What I'm trying to do is strike a balance between triteness and greatness." In the case of Kilimanjaro, it would seem Cope & co. erred on the side of greatness.

(La) luna Lexicon:

1980s,

Album,

Compilation,

Julian Cope,

Kraut-Rock,

New Wave,

Peel Sessions,

Post-Punk,

Psychedelic,

Teardrop Explodes

Thursday, August 25, 2011

Sex Pistols- "God Save the Queen" Video (1977)

No future indeed! Seems to me this song is even more relevant now than it was 35 years ago. In a world rife with bankrupt governments and communities being overrun by the spreading cancer of corporatization, I feel this way about 90% of the time. The other 10% is pure escapism.

(La) luna Lexicon:

1970s,

John Lydon,

Public Image Ltd.,

Punk,

Sex Pistols,

Video

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

Tim Buckley Series, #9: Tim Buckley- Works in Progress (1999) / The Dream Belongs to Me: Rarities & Unreleased 1968-1973 (2001) MP3 & FLAC

"How can my giving find the rhythm and time of you, unless you sing your song to me? "

Lee Underwood: "Right from the beginning, Tim moved me deeply with his music, his attitude, his intelligence and sense of humour. I played guitar with a number of people back then, but he was different. He was not afraid of change. He kept me and the other musicians on our toes. When he moved into this avant-garde or modern classical dimension, I felt both challenged and thrilled. It was one of the most exciting times of my life." Tim Buckley's creative restlessness can best be gauged through the meteoric arc of his work over the course of his first three albums. From the tentative beauty of his overly mannered debut to the stunningly gorgeous Folk songs of Goodbye and Hello to the Jazz inflected explorations of Happy Sad, Buckley's approach in the studio bore the mark of his iconoclastic tendencies and mirrored the increasingly improvisational nature of his live performances. Once, when asked to what extent his music had changed, Buckley responded, "It's not for me to judge. I'm living too close to it. It's a transition. I have to be ruthless and say what is happening. I'm not sentimental over old songs. I'm constantly writing. The main thing is the music." Buckley's "ruthless" need to push boundaries first came to the surface in an explicit way midway through the 1968 recording sessions that would eventually yield Happy Sad. Early on, Buckley and his band recorded a number of the songs that ended up on the final album, but they did so utilizing traditional Folk-oriented arrangements, nearly all of which were quickly abandoned as the sessions took a very different turn. Most of this material was thought lost, but it was eventually rediscovered in the early nineties, a selection of which materialized in the form of Works in Progress at the end of the decade. While Works in Progress is, for the most part, an album of outtakes, it is nearly as essential as Buckley's studio albums, for, not only does it offer a rare glimpse into his creative process in the studio, but, more importantly, it is comprised of a gorgeous set of songs such as "Danang" and "Ashbury Park," which ended up on the final album as parts of a longer composition, "Love from Room 109 at the Islander (On Pacific Coast Highway)." Both sound as though they would have been revelatory stand alone tracks. And then there's the amazing rendition of "Song to a Siren," one of Buckley's best songs, which would end up appearing on Starsailor in a vastly different, less straightforward, arrangement. This is the song Buckley played during his now-iconic appearance on The Monkees after having been invited by his old friend Mike Nesmith: "They asked me to sing on the show. I went along and there was Mike in his mohair suit, and I turned up in working shirt and trousers. Mike said, 'Hey, you're still wearing the same old clothes.' I replied, 'Yes, and I'm still singing my own songs.'"

(La) luna Lexicon:

1960s,

1970s,

Acoustic,

Album,

Chamber-Pop,

Compilation,

FLAC,

Folk,

Folk-Rock,

Funk,

Jazz,

MP3,

Singer-Songwriter,

Tim Buckley,

Vocals

The Damned- "Smash It Up" Video (1979)

Possibly the most underrated band of the original UK Punk scene

(La) luna Lexicon:

1970s,

Captain Sensible,

Damned,

Dave Vanian,

Punk,

Video

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

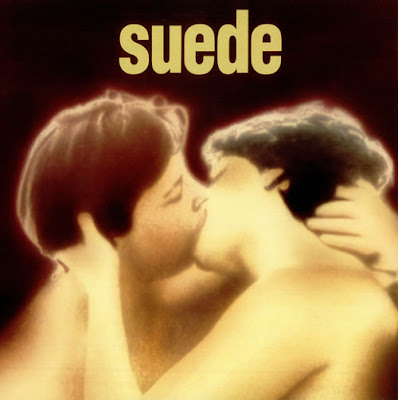

Suede- Dog Man Star (1994) Deluxe Edition (Bonus Disc + DVD Audio Rip) MP3 & FLAC

"And oh if you stay, I'll chase the rainblown fields away. We'll shine like the morning

and sin in the sun."

Like The Smiths before them, Suede, in its early and best incarnation, was built around the creative (and increasingly personal) tension between its two principal members: vocalist & lyricist Brett Anderson and guitarist Bernard Butler. Looking to blend the theatricality and subversive sexuality of early seventies British Glam with the dark edginess of Post-Punk as a response to the Shoegaze scene that was profoundly devoid of both, Anderson & Butler were able to run counter to nearly every prevailing early-nineties trend in alternative music while fashioning what was to become one of the most successful debut albums in British music history. The two had become close friends after the exit of Justine Frischmann from the band in 1991 (she had dumped long-time boyfriend Anderson in order to take up with Damon Albarn of Blur); however, it was during the two 1993 American tours in support of their debut album, Suede, that the seeds for the dissolution of Anderson and Butler's working relationship were sown. Butler, grieving the death of his father and increasingly disenchanted with the band's indulgent lifestyle while on tour, became an alienated figure in the band. Even with the success of the ironically titled stand-alone single "Stay Together," tensions between Anderson and Butler only increased once work commenced on Suede's follow-up LP, Dog Man Star, which, despite the overwhelming enmity swirling about during its creation, is justly considered Suede's masterpiece. Battling endlessly with producer Ed Buller and demanding a lengthier, more improvisational approach to many of the songs (for example, "The Asphalt World" was initially 25 minutes long and reportedly included an eight minute guitar solo!), Butler was eventually compelled to quit the band before the completion of the album. In hindsight, Anderson claims Butler's exit was inevitable given the dynamic and volatile nature of their creative partnership: "He's that kind of artist, Bernard. He has to experience tension and strife in order to do what he does. And I guess that's fine because it makes him what he is. But I do think that it was a tragedy, him leaving, because there was still a lot of gas left in the tank. I have no doubt we could have gone on to achieve something quite extraordinary if he'd hung around." Bernard Butler: "I felt I couldn't go any further with it, musically. We were just never in the studio making music; there was so much else going on. I was always on my own, writing stuff that was getting wasted. Brett was too busy partying. When it came to recording [Dog Man Star] there were so many things I wanted to do with these songs I'd spent an awful long time trying to mould, working out ideas and trying to challenge myself and challenge the band, and I just heard too many times, 'No, you can't do that.' I was sick to death of it." While Butler would ultimately disown Dog Man Star, it is hard to argue against the album's brilliance; if it is the product of the band's (or Anderson's) solipsistic withdrawal into its own pathos-drenched interiors, it is a withdrawal sketched in the kind of lush melancholy and artistic excess that hadn't been seen or heard from since the height of the British Glam-Rock movement. While largely eschewing the Glam-crunch that characterized much of the debut album, Dog Man Star is bathed in hazy, almost hallucinogenic, textures that echo Anderson's often oblique lyrics, which were directly inspired by his growing appetite for drug-induced states of altered consciousness: "I was actually having visions of Armageddon and riots in the streets and inventing strange things, living in this surreal world [....] I was kind of aware that everything was getting slightly strange. I was quite into all these people that had visions and were slightly off their nuts, people like Lewis Carroll. I was quite into that whole idea of becoming the recording artist as lunatic. I was quite into that extremity, but I was definitely living it. It was good fun!" The album was greeted with a chorus of critical praise upon its release, but failed miserably at replicating the commercial prowess of its predecessor. As such, Dog Man Star is often described as an unfocused artistic failure, but nothing could be further from the truth; in fact, it just might be the most ambitious and enduring work to come out of the U.K. during the nineties.

(La) luna Lexicon:

1990s,

Album,

Bernard Butler,

Brett Anderson,

Brit-Rock,

Compilation,

Glam-Rock,

Post-Punk,

Suede,

Video

Sunday, August 21, 2011

Suede- "The Wild Ones" Video (1994)

Here's a taster for what's coming next...

(La) luna Lexicon:

1990s,

Bernard Butler,

Brett Anderson,

Brit-Rock,

Glam-Rock,

Post-Punk,

Suede,

Video

Saturday, August 20, 2011

Ramones- S/T (1976) MP3 & FLAC

"They're piling in the back seat, they generate steam heat, pulsating to the back beat,

the Blitzkrieg Bop."

the Blitzkrieg Bop."

Joey Ramone: "When we started, we were all disgusted with everything on the radio and the state of rock and all the b.s. It wasn't what we grew up with, and it wasn't what we loved and knew as rock. It wasn't Elvis and it wasn't the '60s, the revolutionary time in the history of rock 'n' roll when so many different styles and things went down and were accepted. Even The Trashmen were accepted. There was the psychedelic thing and T. Rex. In the early '70s there were The Stooges and Elevator, but after '73 or so there was nothing but disco shit, even heavy metal had a corporate sound [....] Everything was safe." While it wouldn't be accurate to say the Ramones "invented" Punk, as there were certainly precursors who had a hand in creating the template for the Punk sound such as the aforementioned Trashmen, The Stooges, MC5, The Velvet Underground, The New York Dolls and others, it is accurate to say that the Ramones were the first band to take the D.I.Y. approach of mid-sixties Garage-Rock to an entirely new level by stripping the music down to its primal components: three guitar chords, relentless tempo, a basic melody and a fuck-all attitude. Tommy Ramone: "By 1973, I knew that what was needed was some pure, stripped down, no bullshit rock 'n' roll." Hailing from a middle-class neighborhood in Queens, New York, the original members of the Ramones had dabbled in high-school garage bands for years before forming the band in 1974 and soon thereafter began playing clubs such as CBGB, which were quickly becoming a catalyst for a new underground music scene that, by the end of the decade, would change the face of rock music. Punk Magazine co-founder "Legs" McNeil: "They were all wearing these black leather jackets. And they counted off this song. And they started playing different songs, and it was just this wall of noise [...] they looked so striking. These guys were not hippies. This was something completely new." By 1975, the Ramones were the darlings of the New York underground music press, something that eventually brought them to the attention of Sire Records owner Seymour Stein: "I saw nothing punk in the Ramones. I saw a great band. To me they were a bit influenced by ABBA and Brian Wilson and The Beach Boys. Sure they were quite unique [...] they wanna be called punk that's fine, but they were a great band." After auditioning for Stein and subsequently signing with Sire, the Ramones set about recording their eponymous debut LP, which, despite being recorded in less than a week on a budget of not much more than $6000, turned out to be a game-changer. Ramones begins with the band in full throttle until Joey Ramone's voice leaps into the mix chanting the famous line, "Hey, ho, let's go!," that kick-starts the band's anthemic "call-to arms," "Blitzkrieg Bop." While it's nearly impossible to hear this song the way it must have sounded in the dire musical context of 1976, it is clear that the Ramones, by taking a basic pre-British invasion rock sound and pushing the tempo and delivery into hyper-gear, created something unprecedented. While the simplistic lyrics wouldn't be out of place in the mouths of a '50s-era frat party band, Joey Ramone's aggressive yet abbreviated delivery and the band's relentless I-IV-V thrash behind him lays down an aesthetic blueprint that would pretty much remain unchanged, even in the context of hardcore Punk. While more or less ignored commercially in the U.S., the Ramones, as a result of their July tour of England in 1976, exercised an incalculable influence on the music revolution that was beginning to take hold in the U.K. at the time. Joey Ramone: "We were attracting all this royalty and all the people who would later become The Sex Pistols and the rest. They came to the sound check and told us they formed their bands after hearing our album. When we left England, the whole British punk scene kicked off."

Friday, August 19, 2011

A Few Noteworthy Changes to Recent Posts

Hello Everyone,

I've made two important changes to a couple of recent posts, which you may want to check out:

For Tim Buckley Series, #8: Tim Buckley- Happy Sad (1969), I have replaced the links for the 1989 Elektra Edition with links for the 2010 Japanese SHM-CD Remastered edition. Enjoy!

For Suede- S/T (1993) Deluxe Edition, I have added a 31-track audio FLAC rip of the bonus DVD containing two live recordings (Live at Leadmill & Love and Poison)

I've made two important changes to a couple of recent posts, which you may want to check out:

For Tim Buckley Series, #8: Tim Buckley- Happy Sad (1969), I have replaced the links for the 1989 Elektra Edition with links for the 2010 Japanese SHM-CD Remastered edition. Enjoy!

For Suede- S/T (1993) Deluxe Edition, I have added a 31-track audio FLAC rip of the bonus DVD containing two live recordings (Live at Leadmill & Love and Poison)

(La) luna Lexicon:

FLAC,

MP3,

Suede,

Tim Buckley

Ramones- Live at the Rainbow Theatre, London, UK, Dec. 31, 1977

The Ramones were a Punk band even before there was a name for such a thing, and although they weren't the only precursors to the UK Punk movement of the late seventies, few bands wielded as big of an influence on that revolutionary music scene. The following are excerpts from the Ramones' legendary UK concert on New Year's Eve 1977. Hey Ho, let's go!

Note: For a full frontal aural assault, play all three clips simultaneously at maximum volume ;)

Note: For a full frontal aural assault, play all three clips simultaneously at maximum volume ;)

(La) luna Lexicon:

1970s,

Garage-Rock,

Punk,

Ramones,

Video

Velvet Underground Series, #2: The Velvet Underground & Nico- S/T (1967) / The Velvet Underground & Nico Unripened: The Norman Dolph Acetate (1966) / Yesterday's Parties: Exploding Plastic Inevitable (2005) MP3 & FLAC

"I'll be your mirror, reflect what you are in case you don't know."

Simply put, The Velvet Underground & Nico was a game-changer that, over the course of four+ decades, has served as a guidebook for everything from Glam-Rock to Punk to Industrial and beyond, a deceptively unassuming album whose particular effect was best summed up in Brian Eno's famous pronouncement: "The first Velvet Underground album only sold 10,000 copies, but everyone who bought it formed a band." As the album cover suggests, the back-story of The Velvets' debut is very much about their brief stint as members of Andy Warhol's Factory, for it was through Warhol's mentoring and patronage that they were able to record (a now legendary) album that they themselves never thought would happen. However, from the beginning of their association with Warhol, there was conflict. Paul Morrissey, an avant-garde filmmaker and factory regular, convinced Warhol that The Velvets needed a more appealing lead singer, as Lou Reed was prone to appearing withdrawn and abrasive on stage. German fashion model and fledgling singer Nico, whom Warhol had used in a few of his films, most notably, Chelsea Girls, was Morrissey's recommendation to Warhol, who in turn set about convincing Reed and John Cale to accept Nico as the band's "chanteuse." Despite their hatred for the idea, Reed and Cale were eventually persuaded to not only accept Nico into the band, but to write a few songs specifically for her; being the intelligent opportunists that they were, they likely realized that being given new instruments, free rehearsal space, food, drugs, sex (of all kinds), and Warhol's pop-art cache were perks that few, if any, bands could ever dream of enjoying. Despite all this, at their first rehearsal with Nico present, the band reportedly drowned her voice in guitar noise every time she tried to sing. As Sterling Morrison once revealed, Nico was often a detrimental force within the band: "There were problems from the very beginning because there were only so many songs that were appropriate for Nico, and she wanted to sing them all [....] And she would try and do little sexual politics things in the band. Whoever seemed to be having undue influence on the course of events, you'd find Nico close by. So she went from Lou to Cale, but neither of those affairs lasted very long." Warhol's first major project involving The Velvets was a multimedia exhibition called the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, which involved the band playing in front of a silent 70 minute black & white film entitled The Velvet Underground & Nico: A Symphony of Sound.

Performing in the EPI allowed The Velvet Underground to regularly explore and indulge their interest in musical improvisation, a trait that would be put to use soon thereafter while recording their debut album. In 1966, the first step a band would typically take before recording an album was securing a recording contract. In the case of The Velvets, Warhol decided instead to finance the album himself with the help of Norman Dolph, a Columbia Records Sales Executive who hoped Columbia would ultimately agree to sign the band and distribute the record. In mid-April 1966, after much rehearsing and endlessly working on new arrangements intended to accurately reflect the innovative approach they had honed earlier that spring playing in the EPI, The Velvets entered an old, decrepit recording studio in New York City with Warhol as ostensible producer to record an acetate that would be peddled to various record companies. Lou Reed has clarified Warhol's role during the recording sessions: "Andy was the producer and Andy was in fact sitting behind the board gazing with rapt fascination at all the blinking lights. He just made it possible for us to be ourselves and go right ahead with it because he was Andy Warhol. In a sense he really produced it because he was this umbrella that absorbed all the attacks when we weren't large enough to be attacked. As a consequence of him being the producer, we'd just walk in and set up and did what we always did [....] Of course, he didn't know anything about record production, he just sat there and said, 'Oooh that's fantastic,' and the engineer would say, 'Oh yeah! Right! It is fantastic isn't it?'" Despite the austere recording conditions, The Velvets made the most of the opportunity. The result, known as the Norman Dolph Acetate, ended up being roundly rejected by Columbia who didn't feel the band had any talent (ditto Atlantic and Elektra); however Morrissey managed to sell it to Verve/MGM, who promptly decided to sit on it until the following year because they had just released another "weird" album, Freak Out by The Mothers of Invention and weren't quite sure how to market The Velvets. The delay gave the band a chance to rerecord a few songs under better conditions in Los Angeles while on tour as part of the EPI and to record some new material (including "Sunday Morning") with Verve staff producer Tom Wilson in New York.

An often overlooked characteristic of The Velvet Underground & Nico is the album's sonic diversity. At the time, The Velvets were derogatorily referred to as an "amphetamine band"; they were especially reviled by the so-called "flower children" of the San Francisco music scene who saw the band as excessively dark and out to destroy the last shreds of rock music's innocence. For the 10,000 or so who actually bought the debut album when it was released, they were treated to a varied and uncompromising journey into the nether regions of the growing counter-cultural phenomenon. Not surprisingly, drug-culture steps forth front and center in the form of the album's then-scandalous centerpiece, "Heroin," which features some of Reed's most brilliant lyrics, equally evocative of a love-letter and a suicide note to the song's namesake. In addition, the song's slowly building dynamic mimics the effect of heroin as it hits the bloodstream, thus lending even more emotive power to the lyrics. On "I'm Waiting for the Man," Reed's lyrics treat the listener to the other, even darker side of heroin addiction: the perpetual need to score more skag: "I'm feeling good feeling so fine, until tomorrow but that's just some more time." The song's grimy, staccato feel provides a powerful counterpoint to the dreamy insularity of "Heroin." Much to her chagrin to be sure, Nico ended up with only three songs on the album, all of which are gorgeously off-center due to her singular vocal style. The album is at its most innovative and confrontational on the more avant-garde songs such as "Venus in Furs" and "The Black Angel's Death Song," both of which make heavy use of Cale's haunting electric viola. Not long after the release of the album, the relationship between Warhol and The Velvets began to badly deteriorate due to contractual issues relating to the distribution of album royalties as well as Warhol's decision to focus (again, at the urging of Morrissey) on Nico's solo career. In hindsight, The Velvet Underground & Nico can be viewed as an early death-knell of the hippie movement; as such, it is an abrasively avant-garde, unprecedentedly literate, unflinching existential journey into the dark soul of the sixties, while simultaneously functioning as a harbinger of nearly every underground music scene that has followed in its wake.

(La) luna Lexicon:

1960s,

Album,

Andy Warhol,

Art-Rock,

Avant-Garde,

Bootleg,

FLAC,

Garage-Rock,

John Cale,

Lou Reed,

Maureen Tucker,

MP3,

Nico,

Psychedelic,

Velvet Underground

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Internet Blacklist Legislation

Hello All,

There's good news and bad news on the internet censorship front. As it is always a good practice, I'll start with the good news:

From PC Magazine:

"Under the Digital Economy Act, officials were allowed to ask the court to block Web sites dedicated to copyright infringement. A review of that law, however, 'concluded the provisions as they stand would not be effective, according to U.K. communications regulator Ofcom (Office of Communications). As a result, "the Government will not bring forward the Act’s site-blocking provisions at this time.'"

Yes, the key words are "at this time," but clearly there are major questions about the viability of such censorship-oriented legislation. Unfortunately, the chorus of sycophants and bootlickers called the U.S. Congress is planning its own version of such a law:

The Internet Blacklist Bill -- S.968, formally called the PROTECT IP Act -- would allow the Department of Justice to force search engines, browsers, and service providers to block users' access to websites that have been accused of facilitating intellectual property infringement -- without even giving them a day in court. It would also give IP rights holders a private right of action, allowing them to sue to have sites prevented from operating.

There's good news and bad news on the internet censorship front. As it is always a good practice, I'll start with the good news:

From PC Magazine:

"Under the Digital Economy Act, officials were allowed to ask the court to block Web sites dedicated to copyright infringement. A review of that law, however, 'concluded the provisions as they stand would not be effective, according to U.K. communications regulator Ofcom (Office of Communications). As a result, "the Government will not bring forward the Act’s site-blocking provisions at this time.'"

Yes, the key words are "at this time," but clearly there are major questions about the viability of such censorship-oriented legislation. Unfortunately, the chorus of sycophants and bootlickers called the U.S. Congress is planning its own version of such a law:

The Internet Blacklist Bill -- S.968, formally called the PROTECT IP Act -- would allow the Department of Justice to force search engines, browsers, and service providers to block users' access to websites that have been accused of facilitating intellectual property infringement -- without even giving them a day in court. It would also give IP rights holders a private right of action, allowing them to sue to have sites prevented from operating.

Short of armed insurrection, the only way to prevent such legislation from being passed on behalf of big business and the entertainment industry is to make our voices heard loud and clear to the sheep on the hill. To do so, please click the link below:

(La) luna Lexicon:

Internet Censorship

Wednesday, August 17, 2011

Andy Warhol's Exploding Fantastic Inevitable Featuring The Velvet Underground & Nico (1967)

Andy sure could throw a party. Now where did I put my whip?

(La) luna Lexicon:

1960s,

Andy Warhol,

Art-Rock,

Garage-Rock,

John Cale,

Lou Reed,

Maureen Tucker,

Nico,

Psychedelic,

Velvet Underground,

Video

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

Suede- S/T (1993) Deluxe Edition (Bonus Disc + DVD Audio Rip) MP3 & FLAC

"I was born as a pantomime horse, ugly as the sun when he falls to the floor."

Suede always seemed an odd choice for poster boys of the "Brit-Pop" movement; far more rooted in early-seventies Glam than mid-sixties guitar-pop, far more gloomy Manchester than jingle-jangle "Madchester," few bands had inspired as much hype before releasing their debut album (including being featured on the front cover of Melody Maker), and fewer still had ever delivered on the hype the way Suede did. Quite literally marrying the androgyny & excess of Ziggy-era Bowie to the dark working-class romanticism of The Smiths, Brett Anderson, Bernard Butler & co. couldn't have been more out of step with the music trends dominating London and America during the early-nineties; however, Suede possessed a magnetic stage presence that was rare in an era known for its shoegazing. As one music journalist put it: "They had charm, aggression, and [...] if not exactly eroticism, then something a little bit dangerous and exciting." After parting ways with original member Justine Frischmann who would later resurface as the lead singer of Elastica, Suede issued a slew of successful singles throughout 1992 and early 1993 before releasing its eponymous debut album, which promptly became the most successful debut in British music history (only to be eclipsed by Oasis a year later). Drenched in the same literate nihilism, polymorphous perversity, and theatrical pretensions that made Bowie's early work feel so dangerously compelling, Suede, nevertheless, has a distinctive feel all its own due to the palpable creative tension between Anderson and Butler that is evident throughout the album, a dynamic rivalry, somewhat reminiscent of Morrissey and Johnny Marr, that would result in Butler's acrimonious exit the following year. From brilliant Glam-anthems such as "So Young" and "The Drowners" to the sultry gloom of songs such as "Pantomime Horse" and "Sleeping Pills," Anderson's preening, "mockney" lead vocals intricately intertwine with Butler's lush, molten lava guitar leads, spinning a web of hazy, melancholy decadence that lends the music a certain sense of grandeur dressed up in Punk attitude and Glam-inspired androgyny. Regarding the latter, Anderson, like Bowie before him, sensed the mystique of ambiguity: "Too much music is about a very straightforward sense of sexuality [....] Twisted sexuality is the only kind that interests me. The people that matter in music [...] don't declare their sexuality. Morrissey never has and he's all the more interesting for that."

(La) luna Lexicon:

1990s,

Album,

Bernard Butler,

Brett Anderson,

Brit-Rock,

Compilation,

Glam-Rock,

Justine Frischmann,

Post-Punk,

Suede,

Video

Monday, August 15, 2011

Iggy Pop- "I'm Bored" (1979) Live on The Old Grey Whistle Test

just found this brilliant clip...

Paisley Underground Series, #21: Rain Parade- Crashing Dream (1986) / Demolition (1991) MP3 & FLAC

"Imagine all of your sorrows have left you behind."

The aptly named Crashing Dream was fated to be Rain Parade's one and only full-length studio album after David Roback's exit from the band, in early 1984, to work on the Rainy Day project with his then-new flame, former Dream Syndicate bassist Kendra Smith. According to many accounts, Roback's departure was an acrimonious one; as fellow Paisley scene icon Steve Wynn recalls, "It would be like me being thrown out of Dream Syndicate [....] I never knew why it happened." Roback's version: "It became a drag. I just had to get away and do something else [....] Musically it wasn't working out." Whatever the reason, Roback's exit left his former band-mates, including his brother Steven, at a crossroads in terms of what direction the band's sound would take without its lead guitarist. In addition, the band faced towering expectations from fans and record execs alike to replicate the brilliance of their classic debut, Emergency Third Rail Power Trip. For the time being, Rain Parade decided to proceed as a four-piece and recorded the Explosions in the Glass Palace EP, which, while missing David Roback's deftly subtle touch in places and showing an occasional proclivity for adopting a more traditional approach to song structure than before, suggested that Rain Parade was not eager to relinquish its place as one of the leading bands of the Paisley scene. Fatefully, it was during this time that Rain Parade made its jump to the majors by signing with Island Records, a move that would lead to the band's demise only two years later. Rain Parade released two albums during it's tenure at Island: a live LP recorded in Japan, Beyond the Sunset, and their final studio album, the aforementioned Crashing Dream, which functions as a strange epitaph for this seminal Paisley band, as some see it as Rain Parade's escape from the commercial ghetto of psych-revivalism, while others view it as another example of a great band sent down the road to creative ruin by a major label taking control of the creative process. Taken on its own terms, Crashing Dream is a consistently good, and occasionally brilliant, slice of late-eighties psych-pop that from the opening track, "Depending on You," suggests the band is looking to cut ties with the hazy psychedelia of its debut. The song's slick production and reliance on studio synthetics is a bit shocking initially given Rain Parade's psych-rock pedigree, but as soon as the vocals and lead guitar appear in the mix, the song begins to take form as a nice piece of shiny Power-Pop. The next track, "My Secret Country," moves in more of a country-rock direction, sounding not unlike a slower number by The Long Ryders, and by all rights, it should have become one of the most memorable anthems of the Paisley scene, but its emotional impact is marred by a meandering bridge and the production, which robs the song of much of its grit. Crashing Dream was unjustly ignored upon its release, and Rain Parade decided to call it quits soon after; however, they did briefly reform in 1988 to record a double album, which never materialized until the release of Demolition in 1991. The first half of Demolition is comprised of an alternate ("as originally intended") version of Crashing Dream, which, if nothing else, suggests that Rain Parade were not as eager to leave their psyche-rock roots behind as the over-produced Island version seemed to indicate. As the true epitaph to this legendary L.A. band, Demolition is both a revelation and a further reason to grieve over the untimely demise of a band that deserved a much better fate.

(La) luna Lexicon:

1980s,

1990s,

Album,

Compilation,

FLAC,

Indie,

Jangle-Pop,

L.A. Underground,

Matt Piucci,

MP3,

Paisley Underground,

Power-Pop,

Psychedelic,

Rain Parade,

Steven Roback,

Viva Saturn

Saturday, August 13, 2011

Rain Parade- "No Easy Way Down" (1985) Live "back across town at one of L.A.'s most fashionable clubs"

If you can put up with the twit interviewer and his ridiculous questions for a spell, the live performance that follows is a winner. This is the Post-David Roback / Eddie Kalwa incarnation of Rain Parade, purveyors of a pretty great brand of psych-pop....

(La) luna Lexicon:

1980s,

Jangle-Pop,

L.A. Underground,

Matt Piucci,

Paisley Underground,

Psychedelic,

Rain Parade,

Steven Roback,

Video,

Viva Saturn

1r0n & Win3- The Cr33k Dr@nk the Cr@dle (2002) / The Se@ & the Rhythm EP (2003) MP3 & FLAC

"Love is a scene I render when you catch me wide awake. Love's a dream you enter though I shake and shake and shake you."

Until a homemade tape made its way into the hands of Sup Pop co-owner Jonathan Poneman (with an assist from the editor of Portland-area art mag Yeti, who had previously included an Iron and Wine song on a Yeti compilation CD), Sam Beam was the perfect embodiment of the "bedroom artist": working as a Miami-area Professor of Film & Cinematography by day, by night writing hauntingly beautiful folk songs as equally grounded in the Delta-Blues as they were Nick Drake. He had been writing songs for the better part of a decade when a friend lent him a four-track recorder, and it was from these homemade demos that Beam's Sub Pop debut, released under the moniker Iron and Wine, was culled. While it's tempting to compare The Creek Drank the Cradle with other contemporary, feathery-voiced, folk-based singer-songwriters (there is a seemingly endless supply of them out there), Beam's debut sounds unique, not only due to the meticulously constructed yet lo-fi pedigree of the songs, the way the album as a whole reaches back to influences that pre-date folk music's 1960s-era heyday in addition to displaying an affinity with idiosyncratic Tahoma artists such as John Fahey and Robbie Basho, but also lyrically, as his use of imagery and symbolism, especially relating to animals, lends the album a singular and affective emotional tenor. On the loping opening track, "Lion's Mane," Beam's hushed, lullaby-esque vocal delivery provides perfect accompaniment to the gentle, woody-sounding acoustic guitar arpeggios and slide guitar accents that dominate the song's minimalist arrangement. Lyrically, Beam tends toward impressionistic images of love's allusiveness, perhaps suggesting, with lines such as, "Love's like a tired symphony to hum when you're awake," that is is inevitably so. Yet, as is the case with many of his songs, an animal symbol, in this case, a lion's mane, is used to interject a particularly ambivalent sense of hope into the narrative. Beam's Delta-Blues influence steps forth loud and clear on Southern Gothic tales such as "The Rooster Moans"; with its plucked banjo and slide guitar, it taps into the creaky mystique of an old 78, which serves as the perfect backdrop to its narrative of a young man's journey toward perdition. Another aspect that sets The Creek Drank the Cradle apart is Beam's astonishingly effective use of over-dubbed vocal harmonies. For example, on the achingly dark "Upward Over the Mountain," he over-dubs additional vocal tracks sung at a higher pitch but buried deeply in the mix; the ghostly effect that results is largely responsible for the song's considerable emotional impact. On his follow-up album, Our Endless Numbered Days, Beam, now with a professional recording studio at his disposal, left behind the charming austerity of his debut, and while the more polished results are often equally impressive, Beam's early songs possess a hazy timelessness that no studio could hope to replicate.

(La) luna Lexicon:

2000s,

Album,

Americana,

FLAC,

Folk,

Iron and Wine,

Lo-Fi,

MP3,

Sam Beam,

Singer-Songwriter

Friday, August 12, 2011

Velvet Underground Series, #1: Dean & Britta- 13 Most Beautiful: Songs for Andy Warhol's Screen Tests (2010) MP3 & FLAC

"Hey, I'm not a young man anymore. I've got five nickels in my pocket, gonna get me some more."

Previous to coming under the aegis of pop art icon Andy Warhol, The Velvet Underground, then comprised of Lou Reed, John Cale, Sterling Morrison & Maureen Tucker, had only been together for a short time, but it was clear from the beginning that they were a different breed altogether. As their first manager, Al Aronowitz once recalled, "They were just junkies, crooks, hustlers. Most of the musicians at that time came with all these high-minded ideals, but the Velvets were all full of shit. They were just hustlers." Warhol associate Paul Morrissey happened to catch one of the first gigs Aronowitz had secured for his presumptive band of hustlers at Cafe Bizarre in Greenwich Village and knew right away that Warhol and The Velvets would be a good fit. Classically trained, John Cale had played in minimalist composer La Monte Young's Theatre of Eternal Music, an experimental collective, also known as Dream Syndicate, that focused on drone music. Lou Reed, after graduating from Syracuse University, had worked as a tin-pan alley song-writer at Pickwick International, but his tastes ran toward far less mainstream musical pursuits. Initially, these musical polar opposites were resistant to working with each other, but a shared fascination with the use of a drone effect in music composition brought them together, along with Reed's Syracuse classmate Sterling Morrison, in a short-lived band called The Primitives, which quickly metamorphosed into The Velvet Underground. When Morrissey returned to Cafe Bizarre a few nights later with Warhol in tow, the latter was treated to a surreal scene comprised of The Velvets, now with Maureen Tucker on drums, playing their tales of S&M and heroin highs to a crowd made up of tourists sipping exotic drinks. Warhol was won over immediately and invited the band to join his Factory. Lou Reed: "To my mind, nobody in music was doing anything that even approximated the real thing, with the exception of us. We were doing a specific thing that was very, very real. It wasn't slick or a lie in any conceivable way, which was the only way we could work with him. Because the very first thing I liked about Andy was that he was very real." While The Velvets benefited immediately from Warhol's patronage, the relationship was soon strained by Morrissey's insistence that the band needed a figurehead that was more visually appealing than the often recalcitrant Lou Reed. German model Nico, who had visted Warhol's Factory the week before, was Warhol and Morrissey's choice. Cale & Reed hated the idea, but given the significant career perks of being aligned with a figure like Warhol, they eventually acceded, and Reed was even persuaded by his benefactor to write songs specifically for Nico, several of which would appear on The Velvets' debut album, funded and ostensibly produced by Warhol himself (more on this story later). During their stay at the Factory, The Velvets were used in a number of ways by Warhol, including providing largely improvisational soundtracks for some of his films and multi-media presentations, the most famous of which was the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, featuring the band accompanying a silent film directed by Warhol titled The Velvet Underground and Nico: A Symphony of Sound, along with dancers, strobe-lights, slide projections, etc.

Dean & Britta- "I Found It Not So (Sonic Boom Remix)" / Screen test #7- Mary Woronov

Another of Warhol's mid-sixties projects was the filming of hundreds of screen tests of various visitors to the Factory (including Nico and Reed) with a stationary 16mm camera using silent, black & white 100 ft. rolls of film at 24 frames per second as well as a strong key light to set the subject in stark relief; these were later arranged into compilations and screened in slow motion at 16 frames per second. Warhol's screen tests were not limited to celebrities, however, as anyone who came into the orbit of the Factory, no matter how briefly, was a possible subject. As he stated in The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, "I've never met a person I couldn't call a beauty [...] I always hear myself saying, She's a beauty! or He's a beauty! or what a beauty! But [...] if everybody's not a beauty, then nobody is." In 2008, The Andy Warhol Museum commissioned Dean Wareham of Galaxie 500 and Luna fame and Wareham's Luna band-mate Britta Phillips to compose music for 13 of the screen tests. In addition to original compositions by Dean & Britta, 13 Most Beautiful: Songs for Andy Warhol's Screen Tests features a cover of Bob Dylan's "I'll Keep It with Mine" and an amazingly effective re-working of an obscure Velvet Underground song, "Not a Young Man Anymore." While Wareham's earlier work with Galaxie 500 suggests a strong affinity for the V.U. aesthetic, which shows throughout the project, his true inspiration here is Warhol himself. Wareham: "You could make a case that he [Warhol] was one of the first punks in two ways. 1) He suggested that anyone could be an artist, and that an artist could try his hand at anything. 2) Punk rock celebrates the commonplace and the ugly, and elevates it, and I think Warhol did the same."

Dean & Britta- "Knives from Bavaria (Spoonful of Fun)" / Screen Test #13- Jane Holzer

(La) luna Lexicon:

2010s,

Album,

Andy Warhol,

Art-Rock,

Chamber-Pop,

Dean and Britta,

Dean Wareham,

FLAC,

Galaxie 500,

MP3,

Velvet Underground,

Video

Thursday, August 11, 2011

Dean & Britta- "Not a Young Man Anymore" (2010) From 13 Most Beautiful: Songs for Andy Warhol's Screen Tests

Here's an ode to one cool mother-fucker

(La) luna Lexicon:

2010s,

Andy Warhol,

Art-Rock,

Chamber-Pop,

Dean and Britta,

Dean Wareham,

Galaxie 500,

Lou Reed,

Velvet Underground,

Video

Wednesday, August 10, 2011

The Stooges- S/T (1969) Deluxe Edition (Bonus Disc) MP3 & FLAC

"Now I'm ready to close my eyes, and now I'm ready to close my mind. And now I'm ready to feel your hand and lose my heart on the burning sands."

The story has been spun endlessly but it never gets old: young James Osterberg, son of a high-school English teacher and baseball coach, raised in the trailer parks of Ypsilanti, Michigan, drummer in a string of local bands during his high-school years (one of which, The Iguanas, would yield his future moniker), University of Michigan dropout, lands in Chicago and plays drums in various blues bands before eventually forming a Garage-Rock outfit called The Psychedelic Stooges with a few former high-school buddies, inspired by Jim Morrison's theatrical antics at a Doors concert in 1967, he transforms himself into Iggy Pop, one of the most fearless and manic performers of the rock era, and his band transforms themselves into The Stooges, who end up rivaling The Velvet Underground as the most influential underground band of the late-sixties / early seventies. Forty plus years after the fact, it's hard to imagine what The Stooges must have sounded like to unsuspecting ears in 1969. While the mid-sixties Garage-Rock movement was certainly an inspiration, The Stooges pushed this movement's scruffier edges to extremes by integrating an unfiltered visceral aggression into their recordings and performances that was quite unprecedented at the time (even relative to bands such as The Who), in effect, drafting much of the blueprint for the Punk revolution that followed less than a decade later. That a former member of The Velvet Underground, John Cale, signed on to produce The Stooges' debut is a good indicator that Iggy Pop & co. were making waves on the underground music scene with their often wildly confrontational live performances (Pop pretty much invented the "stage dive" and regularly used broken glass as a stage prop for acts of self-mutilation). Reportedly, The Stooges were prepared to record five songs, all of which were to include long improvisational passages to mirror the approach of their live performances, but their record label, Elektra, balked at this, requesting that the band record additional tracks (falsely claiming they had more songs, the band had to write these practically overnight in the studio). Over the years, Cale's production has been often criticized for toning down the furor that characterized The Stooges' live performances, and his final mix was ultimately rejected by Elektra (the album was subsequently remixed before its release by Pop and Jac Holzman); however, it's hard to deny the brilliance of what the band was able to capture on tape. From the dirty, distorted wah-wah effect of the opening bars of "1969," it is clear that The Stooges are more interested in tapping into deep wells of primal rage than into pretentious utopian dreams of universal love. With its shuffling Bo Diddley beat and bluesy feel counterpoised to Pop's wonderfully cynical vocal delivery, "1969" functions as an anthemic counter-narrative to the increasingly ineffectual posturings of the psychedelic movement. The message here is "fuck you, I'm bored," and in context, it is a powerful one. And then there's "I Wanna Be Your Dog," a song which seems to drop out of the sky without precedent as if delivered via time machine from a decade into the future- this is the violently stripped-down sound of Punk-Rock being born. From the iconic opening blast of guitar-crunch to the unforgettable descending melody that would go on to influence bands such as Joy Division to Pop's innovatively perverted lyrics, "I Wanna Be Your Dog" is a timeless masterpiece that sits proudly at the side of The Velvet Underground's best work. While The Stooges does get bogged down in places by weak material, especially the strangely out of place psychedelia of "We Will Fall," Ron Asheton's fuzzed-out guitar solos usually show up to save the day. If The Stooges debut wasn't their strongest set of songs (that honor goes to their next album, Fun House), it is, nonetheless, absolutely essential for its valiant attempt to start the Punk revolution nearly a decade early.

(La) luna Lexicon:

1960s,

Album,

Compilation,

FLAC,

Garage-Rock,

Iggy Pop,

John Cale,

MP3,

Punk,

Stooges

Tuesday, August 9, 2011

Dean & Britta- "I'll Keep It with Mine (Scott Hardkiss Remix) (2010) From 13 Most Beautiful: Songs for Andy Warhol's Screen Tests

I'm going to start this series a little unconventionally, but don't worry, we'll cover everything you're expecting and a whole lot more. Enjoy your Nico!

(La) luna Lexicon:

2010s,

Andy Warhol,

Art-Rock,

Chamber-Pop,

Dean and Britta,

Dean Wareham,

Galaxie 500,

Nico,

Video

@nna C@lvi- S/T (2011) MP3 & FLAC

"Hold me down, and hold me close tonight."

Every once in a while, a truly distinct independent artist becomes subject to the hype machine that the music press usually reserves for the pablum that emanates from the major labels. While this can be a blessing for an indie artist in terms of exposure, it can also become a curse in the sense that the hype is often comprised of reductive comparisons to other artists and/or ill-fitting identifications with specific genres. In fact, if there is anything that distinguishes much of the music journalism and music promotion of the last decade or so from that of earlier eras, it is the widespread need to over-define and micro-categorize both artist and artwork alike. Anna Calvi is an apt example of this phenomenon, with soundbites from the likes of icons such as Brian Eno claiming Calvi to be "the best thing since Patti Smith" preceding her like a calling card or a scarlet letter, depending on one's tolerance for hype-induced adjectives and predicates. To be honest, I'm usually instantly turned off by such things, but on rare occasion, there is something about an artist's work that speaks through all the hype and over-exposure, in effect, demanding to be heard on its own terms. Anna Calvi's eponymous debut album speaks in this way loudly and eloquently. Co-produced with Rob Ellis, otherwise known as the drummer for P.J. Harvey, another artist whom the music press is eager to compare Calvi to, Anna Calvi is a lush, Goth-tinged set of torch songs that tap into the same romanticized backwoods-blues template that has been so good to Nick Cave over the years, but with some intriguing sonic wrinkles, such as Calvi's guitarwork, sounding a bit like Django Reinhardt-meets-Tom Verlaine as refracted through a David Lynch film. The album's lead track, "Rider to the Sea," is both a fine tribute to the kind of moody guitar-based soundscapes that Verlaine perfected on Warm and Cool and a clear indicator of Calvi's considerable artistic boldness, as it isn't everyday a debut album begins with what is, for the most part, an instrumental. Calvi's sultry vocals make their first real appearance on "No More Words," perhaps the most understated song on Anna Calvi and arguably the strongest. Here, Calvi creates a sixties pop vibe complete with soft, almost whispered vocals, which belies the song's dark, desolate heart. Another brilliant song is "The Devil," a haunting, soul-searching ballad that reaches for the same type of dust-blown twang as Paula Frazer's early work in Tarnation and features some lovely flamenco-influenced guitar work by Calvi. All hype aside, Calvi's debut is the kind of album to get lost in, lovingly constructed, impeccably recorded, and featuring some of the most vibrantly assured Goth-pop you're likely to hear.

Sunday, August 7, 2011

Television Personalties- "The Painted Word" Video (1984)

Here's a highly influential band from the original Post-Punk era that more people need to know about...

Tim Buckley Series, #8: Tim Buckley- Happy Sad (1969) Japanese Remastered Edition (SHM-CD) MP3 & FLAC

"Oh, when I get to thinkin' 'bout the old days when love was here to stay, I wonder if we ever tried. Oh, what I'd give to hold him."

In an early 1969 New York Times interview, Tim Buckley discussed the impending release of the first of his experimental, Jazz influenced albums, Happy Sad: "You know, people don't hear anything. That's why rock 'n' roll was invented, to pound it in. My new songs aren't dazzling; it's not two minutes and 50 seconds of rock 'em sock 'em, say lots of words, get lots of images. I guess it's pretty demanding." If Buckley's previous album, Goodbye and Hello, had been as close as he was willing to come to playing the traditional role of the socially-conscious folk-singer, then Happy Sad was Buckley leaving behind the expectations of both his fans and his handlers at Elektra, in order to chase a sound that simultaneously tapped into the foundational influences of pop music and progressed beyond the melodic and structural limitations of that music. While clearly bearing the influence of Jazz artists such as Miles Davis and Bill Evans (particularly the modal Jazz of Kind of Blue), Happy Sad also features a noticeable transformation in Buckley's approach to integrating his vocals into the arrangements. On songs such as the gorgeous "Dream Letter," Buckley's voice functions more like a lead instrument taking the basic melody and drawing it out through improvised variations, thus guiding the song (often quite subtly) in unexpected/unfamiliar directions, an approach that became the hallmark of his live performances of the time. Happy Sad also marked the end of Buckley's partnership with lyricist and longtime friend Larry Beckett, who had written many of the lyrics for Buckley's first two studio albums. Gone are the overt political references and literary flourishes, replaced by Buckley's more introspective and impressionistic approach, which is, in turn, given a secondary role in support of the music itself. As Beckett recalls, "He was moving toward a jazz sound, so to have wild poetry all over the map, you'd miss the jazz." The jazz sound Beckett speaks of is evident from the very first track, "Strange Feelin'," which, on one level, is clearly paraphrasing Miles Davis' "All Blues," but the song is also replete with textures quite foreign to straightforward jazz, such as Buckley's 12-string acoustic guitar, a sound that allows the music to retain elements of its folk origins. Lee Underwood's bluesy guitar work is also a distinguishing element that, in tandem with Buckley's other-worldly vocals, lends Happy Sad a unique mix of aching beauty and fearless experimentation. These traits are pushed to extremes on the album's centerpiece, the epic and free-styling "Gypsy Woman," which features Buckley completely set free of the structures and conventions governing Western music. This twelve minute song establishes a floating rhythmic sense borrowed from Indian classical music that allows Buckley to take his vocals into uncharted waters. While Happy Sad was only Buckley's first step toward making music that is, as he said, "pretty demanding," it is arguably the high point of, what was to ultimately become, a four album journey into something quite unprecedented (though it should be mentioned that Fred Neil was a major inspiration). Later albums in this vein, such as Blue Afternoon & Starsailor are certainly classics in their own right, but on Happy Sad, there is a palpable sense of newness, a freedom recently fought for and won, and the beckoning (if only for a brief time) of infinite possibility. Of course, all such things eventually come with a price. Buckley: "My old lady was telling me what she was studying in school- Plato, Sophocles, Socrates and all those people. And the cat, Socrates, starts spewing truth like anybody would, because you gotta be honest. And the people kill him. Ha, I don't know if I'm being pretentious but I can see what happens. It happened to Dylan...I don't know what to do about that."

(La) luna Lexicon:

1960s,

Acoustic,

Album,

Chamber-Pop,

FLAC,

Folk,

Folk-Rock,

Jazz,

MP3,

Singer-Songwriter,

Tim Buckley,

Vocals

Saturday, August 6, 2011

Rock City- S/T (2003) MP3 & FLAC

"I feel like I'm dying, never gonna live again. You better stop your lying and think about what's in the end."

By the time Chris Bell teamed up with Alex Chilton in 1971 to form the nucleus of what eventually became Big Star, Bell had been active on the local Memphis music scene since the mid-sixties. At the tender age of sixteen, obsessed with the sounds of the British Invasion, he played lead guitar for a band called The Jynx, which is how he first crossed paths with Chilton, who regularly attended The Jynx's shows (and even briefly sang for them) before joining The Box Tops along with Jynx bassist Bill Cunningham. Toward the end of the sixties, Bell had gravitated into the orbit of Ardent Studios and its founder John Fry, eventually becoming a part-time engineer at Ardent (he was also attending college at the time). In 1969, Bell, by this point writing his own material, developed a fateful friendship with one of Ardent's full-time engineers, Terry Manning, who, strangely enough, recorded a solo album around the same time, Home Sweet Home, for legendary Memphis R&B label Stax Records, which regularly bought studio time at Ardent. Bell and Manning formed a loose-knit band with a revolving cast of characters (including several future members of Big Star) that was known, at various points, as Rock City and Icewater. As Manning recalls, "During all of this, I, of course had the 'day job' at Ardent Studios: engineering for the rental clients. But when there was free time, John Fry was most gracious in allowing, and helping, everyone to try something new on their own." In essence, what this meant was that Bell and Manning were able to record and mix their own songs using a state-of-the-art recording studio without the support or limitations of a recording contract. The plan was to record an album under the moniker Rock City, which at this point was comprised of Bell, Manning, Tom Eubanks- who contributed the bulk of the songs- and future Big Star drummer Jody Stephens. Despite never having been released until a few years after it was rediscovered in a storage room in 2001, Rock City is an important recording because it provides a detailed glimpse into the formative days of a band that would eventually metamorphose into Big Star; however, more than that, taken on its own terms, the album contains some very good, if occasionally derivative, guitar-pop that every so often hints at something exceptional. An example of the former is the opener, Eubanks' "Think It's Time to Say Goodbye," a solid piece of Power-Pop that, despite limping in places due to Manning's limited vocal abilities, manages to do a respectable imitation of Badfinger. The album's flashes of originality occur when Bell takes center stage, as on "Try Again," a song that would be rerecorded to even greater affect for Big Star's debut, #1 Record. While Bell's vocals are a little shaky in places, they are unmistakably Chris Bell, and the song itself belies its guitar-pop foundation, offering up a dark, soul-searing sense of isolation that is miles ahead of anything else on the album in terms of distinctiveness. While Rock City pales in comparison to the greatness that was just around the corner after Bell jettisoned the modestly talented Eubanks and subsequently brought Alex Chilton into the fold, it nevertheless offers a fascinating glimpse of Bell taking his first significant strides toward the muse that would eventually destroy him.

(La) luna Lexicon:

1960s,

1970s,

Album,

Ardent,

Big Star,

Chris Bell,

Compilation,

FLAC,

MP3,

Power-Pop,

Rock City,

Terry Manning,

Tom Eubanks

Friday, August 5, 2011

Elastica- "Stutter" Video (1995)

Let's take another trip down Brit-pop memory lane. Elastica: certainly not the most original band to ever grace a stage, but they were pretty fantastic at that Post-Punk revival stuff (and were so long before it was the trendy thing to do)

Pauline Murray & The Invisible Girls- S/T (1980) MP3 & FLAC -Thank You Cudawaver!-

"Exteriors are never real, nobody shows just what they feel."

From the barely controlled (but still beautiful) punk rage of "Don't Dictate" to the often convincing Patti Smith-isms of Moving Targets to the lush Post-Punk of her solo debut, Pauline Murray & The Invisible Girls, Pauline Murray proved herself to be one of the most gifted vocalists of the Punk/Post-Punk era, who, in terms of ability, was easily the equal of her closest contemporary, Siouxsie Sioux, but in terms of career fortunes, was fated to play the role of obscure cult artist. After the acrimonious demise of Penetration, whose final album, Coming Up for Air, was a critical and commercial disaster to put it mildly, Murray found herself without a band or a record deal but with a reputation that all but guaranteed her a certain level of creative autonomy on her next project. This project would materialize after a move from Newcastle to Manchester with ex-Penetration band-mate and boyfriend, bass player Robert Blamire. While the move was ostensibly to find a more artist-friendly environment, Manchester also happened to be the home of producer Martin Hannett, who, during the course of the preceding two years, had made quite a name for himself as the sonic architect of Joy Division's iconic albums, Unknown Pleasures and Closer. Hannett's unorthodox recording methods and Svengali-like presence in the production booth had lent Joy Division's work a unique and unprecedented approach to creating a sense of spatiality in the music, something he had borrowed from Dub Reggae artists such as Lee "Scratch" Perry. After deciding to work with Murray, Hannett coupled her with his "house band," The Invisible Girls, which included Hannett on bass, Vini Reilly of Durutti Column fame on guitar, and Buzzcocks drummer John Maher. In contrast to Hannett's better known work with Joy Division, Pauline Murray & The Invisible Girls is, unapologetically, a pop record, but one that dresses its uniformly excellent songs in ethereal textures and dark, often edgy hues. This works to great affect on the opener, "Screaming in the Darkness," which bears the imprint of Hannett's obsessive emphasis on creating space between the various instruments and features one of Murray's most memorable vocal performances, managing to sound fey, melancholic, and stunningly beautiful all at once. And then there's the lovely first single, "Dream Sequence I," one of the poppiest moments on the album to be sure, though Hannett's arrangement is still off-kilter enough to give it some edge. Maybe more so than any other song on the album, "Dream Sequence I" makes it clear that Murray had finally found a sympathetic setting for her soulfully sad voice, especially as she belts out the devastatingly catchy chorus that makes the song impossible to forget. While listening to Pauline Murray & The Invisible Girls more than thirty years after it was first released, it is hard not to wonder how Murray failed to become one of the bigger names of the Post-Punk movement, as much of the album seems anticipatory of (if not a direct influence on) many of the paths Post-Punk was to take later in the decade. Needless to say, this album is, without a doubt, one of the great lost gems of the early eighties.

(La) luna Lexicon:

1980s,

Album,

Dream Pop,

FLAC,

Martin Hannett,

MP3,

Pauline Murray,

Penetration,

Post-Punk,

Vini Reilly

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

Paisley Underground Series, #20: The 13th Floor Elevators- The Psychedelic Sounds of The 13th Floor Elevators (1966) / Easter Everywhere (1967) / Bull of the Woods (1968) MP3 & FLAC

"If you fear I'll lose my spirit like a drunkard's wasted wine. Don't you even think about it;

I'm feeling fine."

I'm feeling fine."